Experimenting with indigenous grapes in Castilla-La Mancha

Looking to the past for the future

Robbie Armstrong

Wednesday 27 April 2022

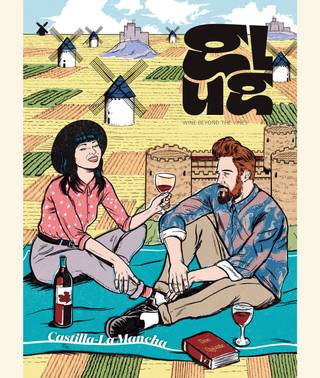

This article is from

Castilla-La Mancha

issue 9

Share this article

There are a staggering 10,000 grape varieties in the world. How then, out of a cast of thousands, have only a handful or two become world famous?

Starting in the late 20th century, the trend for planting international varieties spread across the world, and in many cases, old, traditional vines were ripped up to do so.

One region that knows this all too well is Castilla-La Mancha, an arid but largely fertile elevated plain that accounts for over half of the total wine production in Spain, as well as nine different Denominación de Origen appellations.

With altitudes of between 500–700m above sea level, this is Spanish winemaking at its most extreme; long cold winters juxtaposed with gruelling heat in summer. Locals might describe it as “nine months of winter and three months of hell”, but this is winemaking country par excellence.

The large majority of Spain’s vineyards lie on this tableland around the capital of Madrid, where vast quantities of generic table wine made from international varieties have long been produced thanks to the introduction of irrigation.

Before irrigation, only locally-adapted indigenous grapes which could tolerate hot, dry conditions had been planted here. A La Mancha native, Airén, is a remarkably drought-resistant grape, accounting for almost a quarter of all grapes grown in Spain.

Once maligned due to its association with bulk production, well-made versions of Airén deliver a hit of vanilla and nuttiness, along with creamy peach notes. Like most exceptional whites here, it tends to be oak-aged.

Big, fruity and oak-aged reds tend to dominate the rest of the roster. International varieties such as Cabernet Sauvignon, Petit Verdot and Syrah have remained popular since they were planted in the seventies.

Today, however, there is a new wave of winemakers replanting indigenous varieties, protecting old vines and producing varietal wines. In addition to Airén, native red grapes such as Tempranillo, Garnacha, Bobal and Monastrell have made a comeback.

The latter black-skinned grape makes for beefy, alcoholic, age-worthy reds and is well adapted due to late budding and ripening. Another late-ripener, Garnacha Tintorera (Alicante Bouschet) has olive and black pepper notes. A teinturier, it’s among the very few grapes which have both red skin and red flesh inside.

You can credit local winemaker Elías López Montero, co-owner of Bodegas Verum, for much of the renaissance of native grapes in the region in recent years.

“Interests from different actors had driven our region to become a kind of monster... and the image of the appellation was not good,” Elías explains, reflecting on the period when he joined the family company in 2005.

Verum started to study indigenous grape varieties as part of its Ulterior project, and in 2009, they decided to plant the ones they felt were best suited to their micro-climate: Mazuelo, Garnacha, Albillo Real, Albillo Mayor, Moravia Agria, Tinto Velasco, Malvasía and Graciano.

“Indigenous grapes are important not only to preserve our identity, but to actually create it... sometimes I feel like there is no clear definition of Castilla-La Mancha’s identity, so in Bodegas Verum we help the consumer understand the real roots of this land,” Elías explains.

Tracking old vineyards and recovering forgotten varieties is an important part of the process, which is where Castilla-La Mancha’s Institute of Vine and Wine, IVICAM, comes in. IVICAM is part of the Regional Institute of Agri-Food, Forestry Research and Development (try fitting that on a business card). Its director, Esteban García, has seen the interest in forgotten and minority vine varieties grow in recent years.

Custodians and stewards of their region’s wine culture, this vanguard of viñadores and researchers are championing native grapes that protect the soil, wider ecology and the planet too.

“Varietal biodiversity is a tool to face current challenges due to climate change,’’ Esteban says. Higher temperatures during the ripening season produce lower acidity and a higher sugar content in the berries, so late ripeners provide a much-needed freshness to the wines, and require less water too.

Today, winemakers are producing quality wines from indigenous varietals that are capable of taking centre stage, vying for shelf space alongside better-known international grapes. In viticulture, sometimes the best way forwards is to take a step back.

Share this article