An ode to salt

The only time licking rocks won’t get you called a loser sommelier is when they’re salt crystals

Rachel Hendry

Illustrations:

Heedayah Lockman

Wednesday 27 April 2022

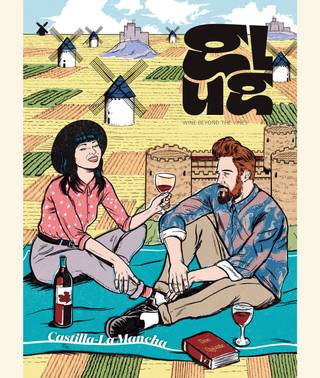

This article is from

Castilla-La Mancha

issue 9

Share this article

Salinity is a tasting note I’ve yet to get my head around. In terms of eating I equate it to the crumbs of ready salted crisps sticking to the prints of my fingers, the glinting flakes embedded into the chocolate chip cookies we serve at work; swallowing mouthfuls of seawater as waves catch me by surprise. But in wine? I’ve yet to fully crack that one.

Salt, the artist scientifically known as sodium chloride, is produced by the reaction of an acid with a base. Sodium on its own is an unstable metal with a tendency to burst into flame (Sodium, I get it), but when it reacts with the poisonous gas chlorine it becomes both a stable and a staple rock, the only kind to be eaten by human kind. A constituent of seawater it can be dissolved into liquid and evaporated by heat—jagged, gritty crystals forming in the warmth of the sun.

As if that wasn’t enough of a résumé, salt is intrinsic to our survival as human beings. Without it we literally cannot breathe, digestion would be a real struggle too and our nerves, muscles and nutritional efficiency are entirely dependent on its presence. So much so that the human being is composed of two hundred and fifty grams of the stuff. Which, if you’ve ever caught a trickle of sweat on the tip of your tongue, shouldn’t come as a surprise.

What did come as a surprise to me, however, was that it is the exact opposite for grape vines. Outside of taste descriptors salinity is used to measure the concentration of salt in soils and any water used for vine irrigation. The more salt present the harder it is for the vines to extract water, and in some cases this can lead to drought. Salt in high levels can also be toxic to the vine’s tissues: leaves can become burnt and in severe cases defoliation can occur.

Salt is also an enemy of alcoholic fermentation. In Mark Kurlansky’s best-selling book Salt: A World History he writes—amongst many wonderful things—of salt as a saviour of food preservation. “Without salt, yeast forms, and the fermentation process leads to alcohol rather than pickles,” he explains. Should salt go anywhere near the winemaking process, yeast wouldn’t stand a chance.

Should salt go anywhere near the winemaking process, yeast wouldn’t stand a chance

Not quite the romantic answer I wanted when I set out to answer the question of: “Is salinity the romantic possibility of tasting the sea?”

Whilst taste and terroir have an intricate and often intimidating relationship, in my mind salinity is as simple as any grapes grown coastally having the following tasting notes:

Like eyes wide, not on your own meal, but on the platter of oysters being feasted upon next to you. Like stripping down to your underwear and trying to match the tide’s rhythm as you wade in, shrieking when you miss a beat. A likeness so captivating you raise your glass to your ear, answering the sea’s call.

Because whilst science and bores may say otherwise, there is so much romance in salt, romance the word salinity just doesn’t quite honour well enough.

Take the magic of wine and food pairings as an example. The more cynical amongst you may have noticed that it is universally impossible to get a bar snack that does not invoke a saline-fuelled desire for another drink. Like a moth to a flame, water is drawn to salt and the more we eat the more we must drink. But there’s more to salt as a drinking companion than meets the capitalist eye.

Any matchmaker worth their salt knows that successful relationships are a balancing act, and our taste buds are no different.

“Salt reduces the impact of acidity,” explains Victoria Moore in her wonder that is The Wine Dine Dictionary. “This is why you can rescue an over seasoned sauce by squeezing in some lemon juice, or apply the same trick in reverse and soften an overly acidic sauce by adding salt.”

It’s an alchemy that forms the basis of some of the most well known wine and food pairings. Chablis and oysters. Champagne and caviar. Fino and olives. Rosé and goats cheese. Any supermarket Italian red with any store bought pizza. I could happily go on.

Try it out for yourself next time you’re in the pub. Order a packet of scampi fries alongside a lemony pinot grigio, some salted peanuts with your merlot or go full holiday mode and pair a packet of ready salted crisps with a rosé spritz. Try a mouthful of one and then a big sip of the other, noting how your mouth responds as saliva forms and thirsts fluctuate. Our taste buds truly are a marvel.

In amongst all of this it is impossible for me to think about salt soothing acid and acid comforting salt in return without thinking about what it means to be loved. I have a personality best described as salty—my mouth cuts sharp but my heart beats gentle—and I find it difficult when the jagged, gritty parts of me snag on those I interact with. I often think of how much easier life would be if I was sweeter, more akin to sugar and I make countless failed attempts to be so. But acid doesn’t just accept salt for all that it is, it welcomes it, compliments it, shows it off in such a way that all the world wants a taste. And I think that’s what good love is capable of. It holds you up to the light, revealing the beauty of all those concentrated, crystallised parts of you.

“Loyalty and friendship are sealed with salt because its essence does not change. Even dissolved into liquid, salt can evaporate back into square crystals” Mark Kurlansky goes on to say, and I highlight the words with such ferocity the page almost tears. Whether we find it in our glass or not, salt is everywhere and I don’t need to fully understand salinity as a tasting note to appreciate it if I find it.

You see, wines from the coast may or may not taste like the ocean, but does the science of it matter if I think about it anyway? Are technicalities of terroir really important if I’m going to fantasise about summer swims and wind swept hair with or without the jargon to prove it? If salt holds everything I need to make me swoon, do I need anything else?

And as far as my personality is concerned, I am slowly learning what compliments me and how to seek it out in others, balancing them in return. If the nature of salt is for its essence to never change then perhaps it’s time I stop wasting my energy in trying to do so.

Share this article