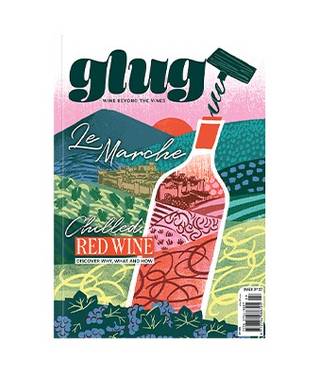

The pride of Le Marche

Katie Mather sings the praises of Verdicchio, the tiny, acidic grape that fuelled the fall of Rome

Katie Mather

Illustrations: Driss Chaoui

Friday 22 September 2023

This article is from

Le Marche

issue 27

Share this article

Verdicchio grapes are small and round, like little tumbled gems hidden amongst the vineyard foliage. Small they might be, but they created a wine that King Alaric I believed helped the Visigoths build their strength—he loaded mule after mule with barrels of the stuff to keep his warriors fit and healthy. It seems to have worked. In 410 C.E the Sack of Rome saw the downfall of the spiritual heart of the Roman Empire to the Germanic Visigoths, and their leader, Alaric, put their victory down to tactics, bravery, and the miraculous effects of this beautiful wine.

Does Verdicchio give me strength enough to sack a Classical capital? Perhaps not, but it does unearth some deep feelings about the flavours I find within each glass, and of the evocative scenes I imagine when I drink it. A delicious wine to drink for fun, Verdicchio can also send me off into my imagination with its subtle complexities and wistful notes of a land I’ve never visited. The region of Le Marche is as distant to me as the Mongolian Steppe, having only ever ventured as far as Venice in my Italian travels, a place no more like Le Marche than my hometown of Lancaster. What I know about the area is what I’ve read in books and seen on winery websites, a green and hilly land of otherworldly limestone caves and turquoise ocean, fields of sunflowers and the sun beating down. Basilica domes and Mediaeval fortresses—and wine, so much beautiful wine. I dream of visiting this underrated place, and of clinking glasses of green Verdicchio in a courtyard in Ancona, where this wine is made and where it was always meant to be enjoyed.

Verdicchio, like Le Marche itself, is overlooked so often that I believe it should be a crime. Punish all Verdicchio-ignorers with no pasta for a month. Unassuming but fragrant aromatics of taut, unpeeled limes and creamy cashews come forth after a moment of swirling—in excellent examples of the wine the aromas are more forthcoming, but it can take a little coaxing. I like to think these shy bottles are homesick. In the best versions I’ve tried I’ve noticed a touch of gorse on the wind, and salted almonds, as romantic as any white wine I’ve tried.

Drinking it is where the fun starts. I don’t think Verdicchio was ever made for smelling. Freshness is its strength, in lemons and marmalade oranges, and a lingering, light bitterness that dances on the tongue with a touch of limestone minerality like a crackling flake of sea salt. It’s this bitterness and minerality that mark Verdicchio out as unique amongst the hundreds of fresh, citrussy Italian whites. Yes, it pairs well with fish, and yes, it’s an easy sipper, but if you want to find depth, it’s there. I feel as though the bitterness of Verdicchio was made for wine drinkers who also love beer, like me. It gives me the kick of refreshment I crave, that in other wines is often lacking in the form of sharp acidity alone. It’s the moreishness I desire, from years of drinking Pilsners and IPAs. If a friend who drinks beer wants to try a wine, I instinctively reach for Verdicchio as one of my recommendations. It just fits.

There are two main Verdicchio regions within Le Marche: Verdicchio dei Castelli di Jesi, and Verdicchio di Matelica. Both are DOCs. Matelica is apparently the valley where King Alaric of the Visigoths bought his wine, and is where Verdicchio is made in a sharper, more acidic style. It’s thought that since the area is warmer than its di Jesi neighbour, this is to do with the minerality and water retention of the clay soils. In Verdicchio dei Castelli di Jesi, close to the Adriatic Sea, the breezy vineyards conversely produce rounder, softer wines, with more herbal notes than in Matelica. In contrast to Matelica’s calcareous clay, di Jesi has limestone soil, full of nutrients, and good drainage thanks to its hilly terrain pocked with cave systems and aquifers. Both DOCs also produce sparkling versions of Verdicchio, which present apple as well as the citrus flavours we love about the grape. In the centre of Castelli di Jesi, so called for its numerous Mediaeval castles, is the Classico heart of the Verdicchio-making region, known as one of Italy’s most prestigious noble indigenous white varieties. The Classico Riserva DOCG Verdicchio made in this region must be aged for no fewer than two years, giving the wine a rich golden colour, and moving flavours of zingy citrus into ripe, warm, juicy oranges and lemons, and even quince and honey. Most good Verdicchios can be aged well thanks to their acidity and complexity, but it’s the soft and supple wines from Castelli di Jesi that have my heart. I can see the vineyards when I drink them, rolling out towards the sea.

To get close to it, you need to taste it for yourself, and see what it’s telling you. For example, this glass in my hand is crying out for a shaving of parma ham, a juicy olive on a cocktail stick, a borage-blue sky, the sound of sparrows. As it opens up, riper oranges find their way into my mouth, their peel tumbling in spirals into a pithy aftertaste of bitter lemon and almond. I should make something with orzo, I think. Maybe today is the day I make that cauliflower alfredo.

Share this article