Pints for heroes

Jo Caird meets the veterans brewing for camaraderie, support and understanding

Jo Caird

Photos:

DropZone Brewery

This article is from

Spain

issue 88

Share this article

Though the psychiatric community recognised post-traumatic stress disorder, or PTSD, as a diagnosis back in 1980, it’s taken a frustratingly long time for mainstream society to get to grips with the condition. Even in the military, which had for decades been dealing with the fall out of ‘shell shock’ and ‘combat stress’, attitudes were slow to change.

By the time Sean Crawford was serving as a Royal Engineer attached to the Parachute Regiment in the 1980s and 90s, PTSD was finally being discussed in the armed forces. “But back then,” he says, “it was, ‘I can't see it. I can't touch it. I don't know what you're talking about. Get a grip’.”

That’s despite the fact that around 8% of UK military veterans with recent active service have reported experiencing PTSD, compared to around 5% of the general population, according to a 2020 study by Cambridge University. The figures are even more striking when it comes to common mental disorders (CMD) a catch-all that includes PTSD along with depression, anxiety and obsessive-compulsive disorder: 23% of veterans report CMD, compared to 16% of the general population.

It was several years after Sean left the services in 2004 that he first came face-to-face with the reality of PTSD, when a friend he had served with admitted to struggling with the condition. “He broke down while talking to me, and that must have taken a lot,” Sean reflects.

And it wasn’t just this one friend who was suffering. “You hear all these horrendous stories of guys taking their lives,” Sean says. “You’ve got to remember, we were in Afghanistan for 20 years. That's a whole generation of military guys. I just wanted to start something to talk about it.”

That “something” is DropZone Brewery, a company that exists to raise awareness of and funding for the mental health challenges facing former servicemen and women. Why a brewery? “In the military you’re either in the bar having a drink at night or you’re having a coffee during the day, but it's all about communication,” says Sean. “I was trying to find a platform where I could create a virtual bar; the idea of picking a beer up and thinking, ‘ah, I remember’.”

While the vast majority of those leaving the armed forces each year (around 14,000 in 2021, though numbers vary considerably) have no trouble transitioning to civilian life, significant numbers find the process challenging, explains James Saunders, a senior peer support coordinator at the veterans mental health charity Combat Stress.

“[In the forces] you work very closely within a team where you're putting your life in other people's hands and you trust them implicitly; you don't find that loyalty out in civilian life,” he says. Post-service careers can be hard to launch because niche military skillsets aren’t necessarily transferable to civilian roles, and then there’s just the general demands of everyday life, from finding accommodation to registering with a GP.

“A lot of them just don't understand how it works in the civilian world,” says James. “That's all taken care of for you in the military most of the time. The military's got a lot better at looking after the soldiers before they leave, but there's still a handful that fall through the cracks and struggle to adjust.”

Social isolation is a common outcome of this “fish out of water” feeling, and one that can exacerbate existing mental health conditions. Social isolation can also be a product of poor mental health itself, says James, because of the “shame and guilt” around avoiding noisy, triggering environments such as supermarkets or sports matches. As Sean puts it, “these guys just want to disappear and crawl under a rock”.

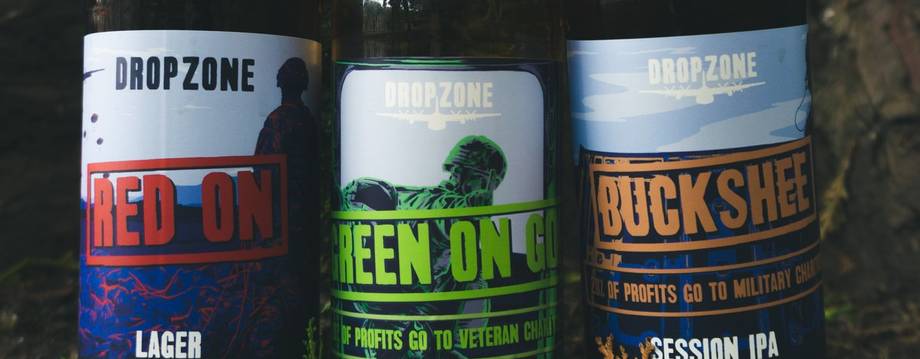

Sean launched DropZone in spring 2021, working with a North Yorkshire brewery (chosen partly because of its proximity to where he was stationed with the Royal Engineers) on a concise product range whose names reference elements of military life. There’s Red On, a lager whose name refers to enemy-on-enemy fire; a session IPA called Buckshee, which is military slang for ‘spare’; and the parachuting-themed cider Green on Go! The brewery donates 20% of all profits to small charities working in the veteran mental health space.

The commercial side of things was tricky to navigate, however. Sean had experience running a business, but not in the food and drink arena (he operates a niche security firm). It soon became apparent that selling beer is “very hard”, he recalls. “You can only sell so much beer to your friends and close connections.” Unperturbed, he added coffee, merchandise and limited-edition spirits to his product range. “Everything is built around how we can create a purpose to communicate again,” he says.

Cask and naval strength rums, whiskies and gins commemorating important military events, such as the 40th anniversary of the Falklands War, are available to buy via the DropZone website, but retail sales are not where Sean sees them having their greatest impact. His main focus, rather, is on having these bottles – a select few of which bear the signatures of some key military personnel – auctioned and raffled at charity events. Sean is chuffed that a complete set of Falklands spirits raised around £3,500 at a recent lunch for the charity Support Our Paras.

“A lot of military people have bought them because it resonates. It has got the power to do that,” he says.

It’s a commendable project – especially when you consider that Sean himself earns nothing from DropZone – but isn’t there something of a contradiction in setting up an alcohol business to raise awareness of the sufferings of a group of people who are unusually vulnerable to alcohol abuse? That Cambridge University study on veterans’ mental health found that while alcohol misuse is an issue in 6% of the general population, the figure among veterans is 11%.

James Saunders of Combat Stress believes that Sean “should be applauded” for his work with DropZone but acknowledges that its premise is potentially problematic. He says: “Most people who leave the military haven't got an issue with alcohol. It's that very few who are suffering with PTSD or other complex mental health issues who, whether they're isolated or not, use alcohol as a coping strategy, that bring an issue.”

The brewery, he goes on, “might attract those types of veterans who have got complex mental health issues or difficulties from their service, because they're looking for that camaraderie”.

Sean is sanguine about this critique, telling me that, apart from being denied advertising space by one of the veterans groups on Facebook, he’s had only one person voice their concern to him on this topic.

His response? “A vast majority of the people that are going to buy this are not suffering from PTSD or dependent upon alcohol, and realise that their donations are going to benefit those who have got PTSD. We're not the cause of [alcohol misuse among veterans]. And we're not going to stop it either, whether or not our beer is there. People who drink are going to do it regardless.”

He's got a point, says James, at least as far as DropZone’s fundraising potential is concerned. “As an organisation, 70% of our money comes from people like him and the general public. Without them, we wouldn't be able to exist.”

Sean says that he gets asked all the time why he went to the trouble of setting up a brewery rather than just donating the equivalent in cash – he’s spent around £30,000 so far, he reckons, between set up costs and direct personal donations.

“Because that's only connecting one journey ‘A’ to ‘B’, isn't it? Everyone that's getting involved along the way, creating that platform, talking – you’re helping more, it's spreading wider.”

Share this article