Modern nature

Robyn Gilmour braves the narrow laneways of Firle to pierce and protect the mythology that surrounds one of the UK’s most revered breweries

Robyn Gilmour

Photos:

Richard Croasdale

Saturday 03 June 2023

This article is from

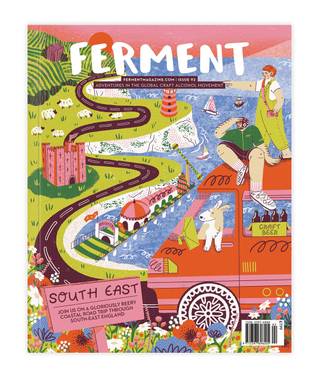

South East

issue 92

Share this article

Too low to be visible from below, what we can see of the coolship – which sits on a mezzanine between the old barn’s rafters and the active production floor – is actually a bizarre and beautiful web of old barrel staves, woven into a structure suspended over the shallow pool. Yeast laden, and deserving of space at any contemporary sculpture gallery, the structure hammers home the natural coexistence of art and science, but also fills me with an almost overwhelming awareness of both the beauty and the brutality of nature.

Burning Sky’s sales manager, David Pritchard, tells me that even with a world renowned team combining decades of experience cannot lay the table for passing yeasts, and cultivate conditions that give fermentation the best possible chance of success, to get the uptake of wild yeast it needs to become beer; “we don’t know whether it’s worked or not until the beer has been in barrel - sometimes for a month or so, and we can see whether fermentation is happening. It's a risk, but that’s just nature.”

That something so small as to be invisible to the naked eye, might have a team of people working for and with it, makes all the history behind the 500 year old estate the brewery sits in seem strangely insignificant, or at least, only as important as the ancient brick and beams that house sleeping yeast. Naturally, Burning Sky has capitalised on this resource and made both the brewery buildings and surrounding verdant fields a part of operations. The cold store, which was originally the room its coolship was kept in, had been a crumbling barn inhabited by horses when owner Mark Tranter found the site. He had to dig out and lay a solid floor, and reinforce the structure of the ruined building with steel beams that essentially rendered the original walls and rafters a shell, draped over a new, more solid structure.

Mark, Burning Sky founder

That was ten years ago now, making Burning Sky one of a handful of UK craft breweries to reach the rare and hard fought decade milestone this year. That said, the experience that informed the intention and concept behind Burning Sky long predates the beginning of the brewery. Mark was a founding member of Dark Star Brewing, and started brewing there in 1996 when operations were still confined to the cellar of Brighton’s esteemed Evening Star. Though he quit the company in February 2013, the seventeen years of hard work he’d put into the brewery no doubt played a part in attracting the interest of Fullers, who acquired the brand in 2018, before itself being bought out by Asahi in 2019.

Being a director at Dark Star, it took Mark six months to disentangle himself from the business, during which time he began work on the project that would become Burning Sky. Coming from a brewery that produced beer on an ever growing scale, barrel aging wasn’t a process that Mark had the time or resources to pursue at Dark Star. Yet his interest in spontaneous and mixed fermentation beers only intensified over many years, and with every visit he paid to Belgium with good friend Eddie Gadds, then of Ramsgate Brewery.

“Eddie is a great guy and a great friend,” Mark says. “We have been to Belgium together a lot over the years, and visited La Chouffe, were lucky enough to get a personal tour from Jean-Marie Rock at Brasserie Orval, and we got really into Lambic and Gueuze. Basically, we started weaseling our way into more and more places, asking more and more questions and occasionally getting some answers”. In spite of all these golden tidbits of information, by the time it came to leave Dark Star, Mark still had no direct experience of brewing wild or mixed fermentation beers. So bizarrely, he went to the US – for just 18 days – to see how the practice of wild fermentation worked in a place with no history or tradition informing its technique.

“I had previously met the founder of Goose Island,” says Mark, “ and I was fortunate enough to spend a couple of days at the brewery’s barrel store. They’d just been bought out by AB InBev and some huge investment had been channeled into the development of their barrel store. From there I visited Revolution Brewing, Avery, caught up with Doug Odell and spent time at Odell’s, then New Belgium, Funkwerks and of course, Crooked Stave. So, that was my demystification of mixed fermentation beers. Whilst waiting in Denver Airport, I did a bank transfer for the deposit on the brewery. I had never had or parted with so much money, I must have been stupid”. I have to laugh, and he gives way to a little grin.

Mark got back to the UK just before building work began on the brewery site in June of 2013, and in September, Burning Sky brewed its first beer. Six months later, operations demanded more space, and Mark took over two old adjacent farm buildings. Since then, the body of Burning Sky has more or less remained the same, which is to say, the brewery has stayed small. Its bottling machine (separate to its canning line) is almost outrageously manual, though David justifiably points out that it’s only used 20-30 times a year, to funnel seasonal releases into champagne bottles, Belgian style. “It only ever takes three or four people to bottle for a day to get the job done, but it makes the product feel a bit more special that every single bottle has been filled and handled by a person.”

So much of Burning Sky’s beer goes into a barrel for anywhere from three months to three years. Depending on when the beer is ready, according to the taste of the blender, it might be further aged over cherries, grape must or elderflower in line with what's seasonally available. Once bottled, it’s allowed to sit for three to four weeks, and be gently warmed if the beer calls for some extra help developing into its final form.

“We brew four or five times a week, and can get up to 10,000L, but we limit it to that,” says David. “We don't want to double brew each day or whatever; it’s about having the time and resources to ensure each beer is done properly, and gets the care it needs… In this way, production has been pretty similar for the last five years and our development is coming through better management and planning of our yearly calendar of seasonal releases.”

In a later conversation with Mark, I ask him about the size of the team, which is just seven strong, and in doing so feel I gain a glimmer of interesting insight into the inner workings of the brewery. “I used to have to work pretty hard at Dark Star, and I carried that over to Burning Sky. Whilst I don’t do so much production now, I like to be busy with my day and I feel that the others do too,” says Mark. “I’d rather be able to pay people as well as we can and keep the product as affordable as possible, than pay someone to do tik tok and other social stuff. I do the Twitter, and occasionally put things on Instagram, but I don’t care too much for heavy social media. It’s beer– a physical thing– drink it whilst talking to your mates, listening to music, or reading a book.”

Depending on your point of view, Mark’s approach to the hard, manual work that goes into producing a complex, natural product might either look like a well-balanced lesson in letting go, or a rare but perfect antidote to capitalist driven alienation. As much as it’s impossible to argue with the forces that dictate whether wort gets spontaneously inoculated, when skill and experience renders fermentation successful, the end product is as simple and complicated as beer, even if Burning Sky is making the best of its kind. Mark seems not only to have accepted this, but embraced the coexistence of excellence and ease, process and product, ancient and modern nature.

Share this article