Patagonian Yeast

Championing Chile's Biodiversity

Robyn Gilmour

Photos:

Patagonian Yeast

Saturday 01 July 2023

This article is from

Chile

issue 93

Share this article

You haven’t felt inadequate and unaccomplished until you’ve spoken to Patagonia Yeast founder, Victoria Lobos. With more strings to her bow than I can count, Victoria has utilised her scientific expertise in the field of fermentation and yeast management to act as consultant to beer, wine, cider, grape ale and kombucha producers, run courses for brewers in microbiology and fermentation management, found The Little Brewing Company, and establish her own yeast lab, Patagonia Yeast.

Her journey to Patagonia Yeast has taken her through some of the world’s most prestigious universities, labs, and biotech companies, but it has also taken her the length and breadth of Chile. Victoria has used the country's extreme temperature and altitude variance to find, isolate and propagate yeasts capable of fermenting beer in conditions that would be detrimental, even fatal, to most brewers’ yeasts.

In the last number of years, you may have heard or read about saccharomyces eubayanus, the cold resistant species of yeast found in Patagonia that’s believed to be the ancestor of lager yeast, brought to Bavaria through the migration of people some centuries ago. This yeast was discovered in a mushroom growing on Patagonia’s south beech trees, and is believed to have hybridised in such a way that its progeny inherited eubayanus’s cold resistance. Victoria, however, has been searching for yeasts that, without intervention, are able to ferment effectively in a wide range of temperatures and in some cases, produce unique esters and phenols.

So far, she’s isolated a yeast from a species of cactus that can be found in the Atacama Desert, another species originating in a nut bush, and a third strain – which is used in Patagonia Yeast’s IPA and Victoria has appropriately named the Dionysus yeast – that has come from the murtilla fruit, a kind of red berry that grows high up in the Andes.

With the climate in which this berry grows seeing a daily temperature fluctuation of 5-250C, any bacteria, fungi or yeast that coexists with it must be able to function consistently at a wide range of temperatures, a characteristic which – if the popularity of nova and kveik is anything to go by – is desirable in a brewers’ yeast these days. Compounding this, the yeast is also wildly versatile; by not producing bold esters, Victoria tells me this medium-to-high attenuating yeast can bring a gentle balance to everything from a golden ale, to an IPA.

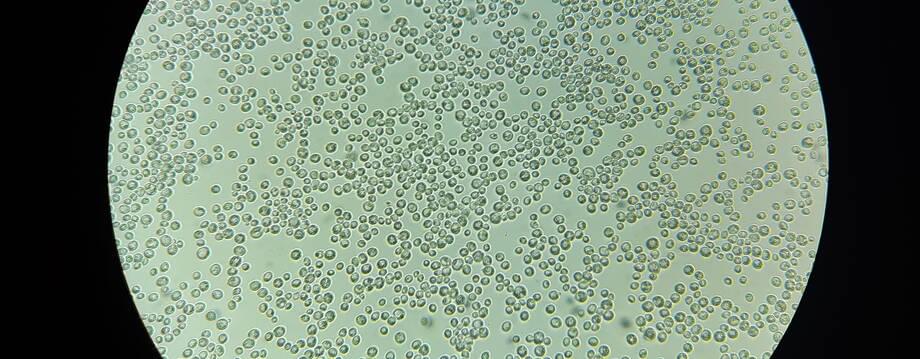

As much as Victoria has used Chile’s unique landscape and climate to guide her search for versatile yeasts, reaching a point at which her findings can be propagated and banked is, by the sounds of it, absolutely agonising. “Before you isolate, you have to collect,” she tells me. “And when you collect, you collect everything – that’s bacteria, yeast, fungi, all kinds of microorganisms – and from there, you have to categorise everything, at which point you’ll have an idea of whether you’ve found what you’re looking for. Then you can validate your findings. It’s a huge process, it took me about three and a half years to isolate my first species.”

With that kind of work going into the isolation of yeast before it’s even banked or propagated, it’s no surprise that Victoria is such an advocate of proper yeast management, and runs courses and workshops with breweries to encourage correct use and treatment. “The yeast is your worker,” she says. “Some breweries think they can use less yeast – because it’s cheaper – and that everything will be fine, but that stresses the yeast, and will cause it to develop scars on its membrane, which is what the yeast uses to eat and detect good food sources. So if you use less yeast to make fermentation cheaper, you’re actually making the yeast you do use less effective.

“Equally, the rate of pitching is so important. Different species will produce different esters and different phenols at different temperatures, so to control this properly you have to change the temperature very slowly, day by day. This is really important when you’re producing different styles of beer; if your yeast makes lots of phenols and you’re trying to make a session beer, you’re going to reduce its drinkability.”

While Victoria is a scientist before she is a brewer, her challenges are the same as Chile’s craft breweries; the issue, as always, is how to communicate the value of craft, and the importance of sustainably investing in the utilisation and celebration of Chile’s immense natural resources and completely unique landscape. Among other things, Victoria says support needs to come from the government.

In combination with high taxes, the infrastructure facilitating the mass importation of key ingredients makes it extremely expensive, if not impossible, for small producers to purchase the smaller quantity of materials they need and can manage. The result is that where a litre of generic, macro beer might cost $1, a litre of craft could cost $10. But as difficult as it might be to compete on price, Victoria can see an ever-increasing appetite for quality.

“You know what though, as scary as the industry can be, I love my life,” Victoria tells me. “I love getting to do this work, and to travel. The image on the label of Patagonia Yeast’s IPA is of a Magellanic Woodpecker, since we just kept running into this bird over the course of the yeast’s isolation. Specifically, while we were collecting samples to take them to the laboratory, this bird was pecking at the trees around us. Because of its habitat requirements this woodpecker is considered, bio-ecologically speaking, as an ‘umbrella’ species, indicating that the areas it's found in are regions of high biodiversity. The Magellanic Woodpecker has come to represent what our research, and many of our collections mean to us. It was our guide bird.”

Share this article