Bird is the word

We speak to White Stork, the ultimate ambassador for Europe’s hidden craft beer gem: Bulgaria

Robyn Gilmour

Photos:

White Stork Beer Co

Saturday 15 November 2025

This article is from

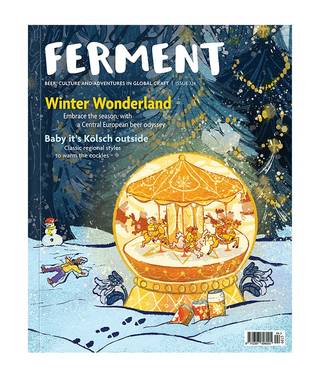

Winter Wonderland

issue 124

Share this article

I have to apologise to Karel Röell, CEO of Sofia’s White Stork Beer Co, for the background of my call. I’m hunkered down in the quietest (and most ragged) corner of my attic room, hiding from the noise of roofers replacing part of a downstairs bay window. Karel isn’t phased; “it’s the same here. The end of summer is coming, so repairs to apartments all over Bulgaria are going at full pace. It’s a bit like Paris here, everybody disappears in July and August, and they come back in September.”

He says that in the past, people used to leave the city and head to the Black Sea to holiday but now, a new motorway connecting Bulgaria with the Greek border means people can get there in two and half hours. This has not been insignificant for Bulgarian hospitality. The sale of macro brands are down in Sofia, and have grown only by a percentage or two by the Black Sea.

Karel is acutely aware of fluctuations in the Bulgarian market, but also how much rides on the outcome of winter and summer seasons on account of White Stork having a bar in Bansko. If you’re unfamiliar with the ski town, please search for some photos — it’s mind-blowingly beautiful in winter, and Karel says that thanks to a progressive mayor, the town is steadily cultivating an attractive summer season.

“They have a rock festival, they have a jazz festival that lasts 10 days, they have an opera festival,” says Karel. “The lineup goes from June to September so it's now extremely busy in the summer.” Sofia is a similarly attractive summer destination, particularly for beer lovers, but Karel says it's still somewhat of a hidden gem, partially on account of it having a complicated history when it comes to brewing, among other things.

“Bulgaria's got a long history of being oppressed,” he points out. “It had its own empire, and then the Byzantines took over, and then the Ottomans took over. They have 500 years of Ottoman Empire behind them, which means more wine and rakia [now the national spirit of Bulgaria, distilled from fermented fruit] and no beer. It was only after the 1880s when they got their independence that they started brewing beer, but even that was mostly due to Czech influence. They’re right down the Danube after all.”

Only the three biggest breweries — Kamenitza, Zagorka, and Shumensko — survived the fall of the Soviet Union

Karel continues to explain that after the second world war, when Bulgaria was under Russian influence, the state took control over all breweries and independent brewing was prohibited — the residue of which lives on today in the fact that it is still illegal to homebrew in Bulgaria. Only the three biggest breweries — Kamenitza, Zagorka, and Shumensko — survived the fall of the Soviet Union, after which point smaller regional breweries could open, or resume operation. Of course, Heineken, Molson Coors and Carlsberg bought over the three biggest breweries as soon as they were able.

This was how Karel found the Bulgarian market in the years before founding White Stork. “It was a black hole,” he says. “There were two craft breweries on the scene, Divo Pivo, which means ‘wild beer’, and Glarus, which was a little bit more commercial, but that was it. There was one craft bar and one shop in all of Sofia, but that was the start of the market, and it was fun.” White Stork was founded in 2013 by a group of homebrewers — infer from that what you will, given Bulgaria’s legislation around homebrewing — with different backgrounds, but who collectively agreed to go down the hop-forward route, to differentiate White Stork from what other domestic breweries were doing.

Karel says he was personally inspired, not by American craft, but by The Kernel. “I did 25 years in London, and when the Bermondsey Beer Mile started to come out of the ground, I wasn't living that far away. I was really attracted to what The Kernel was doing; they were simple beers that were hop-forward, and they experimented with the hops. They really influenced what I did. For example, the first Pale Ale we brought to the market here in Bulgaria was a simple cascade, dry-hopped Pale Ale. We built on that, and were the first ones to bring out an IPA, a hopped stout, session IPA, all that stuff.”

PHOTO: Pivoteka, Craft Beer Mountain Base

White Stork worked like this for its first seven years of life, then, like everyone else, the pandemic forced it to pause, take stock, and reevaluate the way it was working. “We kept that philosophy until 2020, when Covid started, and then moved into thinking, ‘okay, what do the people really want?’” says Karel. This was a common realisation for breweries when the pandemic hit, but how Karel and the team reached this conclusion is quite unique.

As Karel tells it, in the years leading up to the pandemic, White Stork has dipped its toe into the realm of restaurants, and even some nightclubs. “The more I was the guy behind the bar and not the guy making beer, the more I saw that there was more interest in something easy,” says Karel. “We had been the first brewery in Bulgaria to release milkshake IPAs, and put hibiscus and fruits in a beer, but at that point I thought, ‘okay, let's see what we can do with very simple pils’.”

Critically though, after the pandemic, White Stork took over its distributor, Pivoteka, giving the team up-close and personal insight into exactly what people were buying. An ancillary benefit of the takeover was that Pivoteka could draw on White Stork’s longstanding connections with breweries it had already been importing from in small quantities for many years.

From 2016, Karel says White Stork had been imported from Cabinet in Belgrade and Ground Zero in Bucharest, and then later from Mad Scientist in Budapest and The Garden in Croatia — just to inject Bulgaria with a bigger variety of beers, brewed in White Stork’s modern, hop forward style.

Every year on the first of March, people give their friends a kind of white bracelet called a martenitsa

Nowadays, the company — encompassing both White Stork and Pivoteka — is a little more refined, or at least uses each brand to do different things. The “very simple pils” referenced by Karel is brewed under Pivoteka’s name, and called Halla after the folkloric female figure associated with wind in Bulgaria. It makes for a nice cross reference to the White Stork.

“Bulgaria is very much influenced by storks,” Karel begins. “In Western Europe, storks bring babies, but in Eastern Europe, there’s a lot of mythical stories around storks, in which they’re shape shifting creatures. Here in Bulgaria, we get a huge population of storks in March, when they fly over from Africa. So, every year on the first of March, people give their friends a kind of white bracelet called a martenitsa. You’re supposed to wear the bracelet until you see a budding flowering tree or your first Stork, at which point you have to tie the martenitsa to a tree for good health. So, you’ll see a lot of trees in Bulgaria get totally covered in bracelets and the guy with the most friends has got his arm full of bracelets.”

The White Stork, and indeed Bulgaria’s beer scene, might have done some shape shifting over the years, but the brewery also strikes me as one which, come the first of March, is completely dressed in martenitsa. In my mind, that’s what counts.

Share this article